Annotating to extract findings from scientific papers

David Kennedy is a neurobiologist who periodically reviews the literature in his field and extracts findings, which are structured interpretations of statements in scientific papers. He recently began using Hypothesis to mark up the raw materials for these findings, which he then manually compiles into a report that looks like this:

The report says that two analysis methods were used: Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and voxel-based relaxometry (VBR). The relevant statement in the paper is:

“Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and voxel-based relaxometry (VBR) were subsequently performed.”

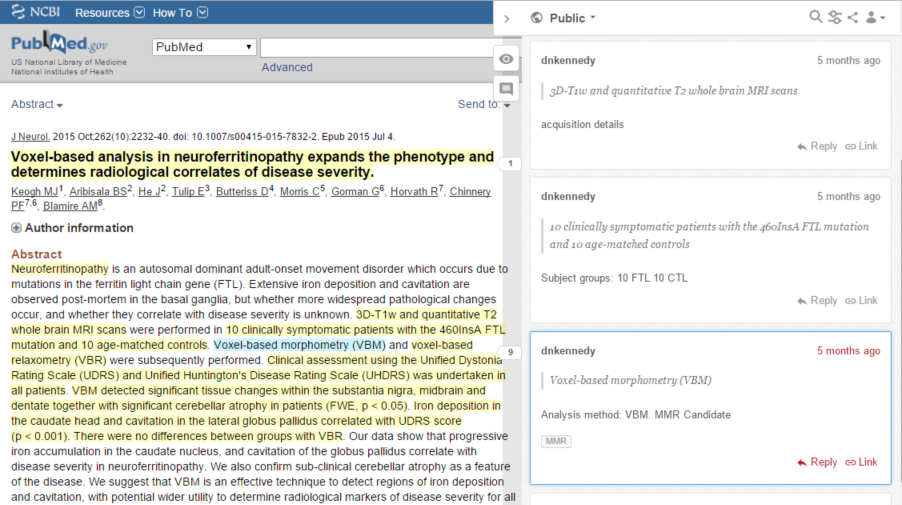

To extract these two facts, Dr. Kennedy annotates the phrases “Voxel-based morphometry (VBM)” and “voxel-based relaxometry (VBR)” with comments like “Analysis method: VBM” and “Analysis method: VBR”. You can see such annotations here:

This was really just a form of note-taking. To create the final report, Dr. Kennedy had to review those notes and laboriously compile them. How might we automate that step? To explore that possibility we defined a protocol that relies on a controlled set of tags and a convention for expressing sets of name/value pairs. Here’s that same article annotated according to that protocol:

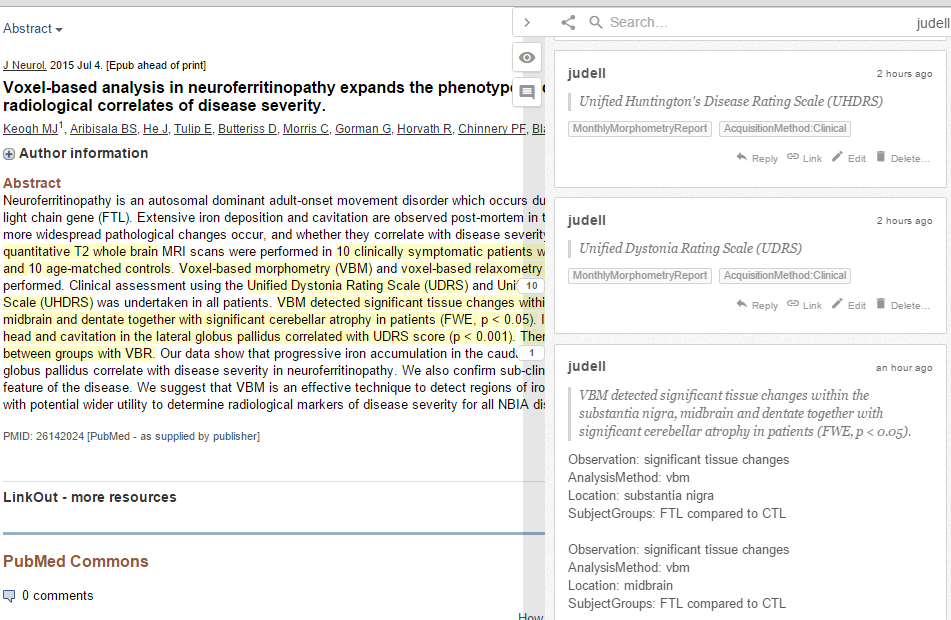

The tag MonthlyMorphometryReport identifies the set of annotations that belong in the report. Although it has no formal meaning, we agreed that the tag prefix AcquisitionMethod: targets that section of the report, and that tags prefixed that way can otherwise be freeform, so annotations tagged with AcquisitionMethod:VBR and AcquisitionMethod:VBM will both land in that section.

Sometimes tags aren’t enough. Consider the statement:

VBM detected significant tissue changes within the substantia nigra, midbrain and dentate together with significant cerebellar atrophy in patients (FWE, p < 0.05). Iron deposition in the caudate head and cavitation in the lateral globus pallidus correlated with UDRS score (p < 0.001). There were no differences between groups with VBR.

It expresses a set of findings, such as “There were no differences between groups with VBR,” and a set of related facts. Here’s how we annotated the findings and the associated facts:

We use Finding:VBM1 for facts extracted from the sentence “VBM detected significant tissue changes within the substantia nigra, midbrain and dentate together with significant cerebellar atrophy in patients (FWE, p < 0.05)” and Finding:VBM2 for facts extracted from the sentence “Iron deposition in the caudate head and cavitation in the lateral globus pallidus correlated with UDRS score (p < 0.001)”.

Given this protocol, a script can now produce output that matches the handwritten report:

Clearly this approach cries out for the ability to declare and use controlled vocabularies, and we aim to deliver that. But even it its current form it shows much promise. In domains like bioscience, where users like Dr. Kennedy are familiar with principles of structured annotation and tolerant of conventions required to enable it, Hypothesis can already be an effective tool for annotation-driven data extraction. Its native annotation and tagging capability can enable users to create useful raw material for downstream processing, and its API delivers that raw material in an easily consumable way.